The Popcorn Champs

The Popcorn Champs looks back at the highest grossing movie in America from every year since 1960. In tracing the evolution of blockbuster cinema, maybe we can answer a question Hollywood has been asking itself for more than a century: What do people want to see?

When Darth Vader first appears in Rogue One, the Star Wars spinoff that became the highest-grossing movie of 2016, he offers a word of advice to the movie’s primary villain, Ben Mendelsohn’s Orson Krennic: “Be careful not to choke on your aspirations, Director.” That line is a pun; Vader has just been using the Force to crush Krennic’s windpipe, and he’s putting the insolent Empire functionary in his place. But you could also read that line as a piece of Disney corporate wisdom. When it comes to Star Wars, Disney is not interested in indulging the aspirations of any ambitious directors.

Ever since Disney got into the Star Wars business with 2015’s massive hit The Force Awakens, the company has had a director problem. Josh Trank, Colin Trevorrow, and the team of Phil Lord and Chris Miller have all been attached to various Star Wars movies, and they have all been removed from those projects. Every so often, Disney will announce that another big-deal director has signed on for further Star Wars movies, and it never seems especially likely that those movies will end up getting made. In a lot of ways, 2019’s The Rise Of Skywalker, the most recent Star Wars film, feels like Disney apologizing to pissed-off fans for the decisions that director Rian Johnson made on The Last Jedi, its predecessor, and attempting to erase those decisions. Disney is simply not willing to spend hundreds of millions to indulge a director’s whims when there’s Star Wars money on the line. When those hired directors fall in love with their own aspirations, Disney chokes them right out.

By most accounts, that’s what happened on Rogue One. For its first film that’s not part of the main Star Wars story arc, Disney brought in the British director Gareth Edwards, a former visual-effects guy who’d directed one small movie, Monsters, and one big movie, Godzilla. Disney went through a ton of different scripts for the film, and when the company wasn’t sure about the end result, they hired another ringer. With Edwards still on board, star screenwriter and Michael Clayton director Tony Gilroy came in, rewrote the film, and reshot a huge chunk of it. Edwards kept his sole-director credit, while Gilroy was named one of the film’s two writers. If Rogue One had a proper auteur, it was probably Disney’s appointed Star Wars overseer Kathleen Kennedy. Or maybe it was Bob Iger, the person in charge of Disney itself. It definitely wasn’t a mere director.

Watching Rogue One, you can clearly see that it’s the result of a messy, slightly incoherent creative process. Certain characters make decisions that don’t really make sense. (Forest Whitaker’s insurrectionist firebrand Saw Gerrera decides to die in an exploding city rather than escape because… he’s tired?) The things that an individual director might make sure to include, the human moments that build plot-catalyst types into fully realized characters, generally just aren’t there. Most of the footage from the first Rogue One teaser trailer isn’t even in the movie; Disney clearly reworked the final product extensively on the fly. But with all that said, Rogue One remains a blast—probably the most deeply satisfying Star Wars feature that Disney has made since the company dropped a few billion on acquiring Lucasfilm.

Maybe the initial idea was just so good that corporate meddling couldn’t ruin it. Before Disney even bought Lucasfilm, John Knoll, a visual-effects supervisor who’d worked on George Lucas’ Star Wars prequels, pitched an idea that basically amounted to a film adaptation of the opening crawl from the original 1977 Star Wars—three vague and sensationalistic paragraphs, fleshed out to more than two hours of movie time. Rather than spending time with the prospective Jedi knights of the Skywalker clan, Rogue One would tell a war story about the expendable soldiers who died to make Luke’s triumph possible in the first place. That fucking rules. That’s hard to mess up.

Disney made smart hiring decisions, too. Edwards didn’t have a ton of experience as a director, and he didn’t exactly have a gift for vivid and memorable human characters, but he could do sheer awe-inspiring scale better than any of his peers. When AT-AT walkers stomp into the frame during the climactic battle of Rogue One, they finally make sense as weapons. They are theatrical monsters, forces of intimidation, things that should not be. Edwards also conveys the mass of the Death Star as it hovers serenely in the sky, preparing to obliterate an idyllic landscape. Where they weren’t satisfied with Edwards’ work, the Disney people brought in Gilroy, one of the most revered writers and plot mechanics in Hollywood, and Edwards said all the right things to the press about the process. Everyone involved clearly wanted Rogue One to succeed, even if they had different ideas about how that might be made to happen.

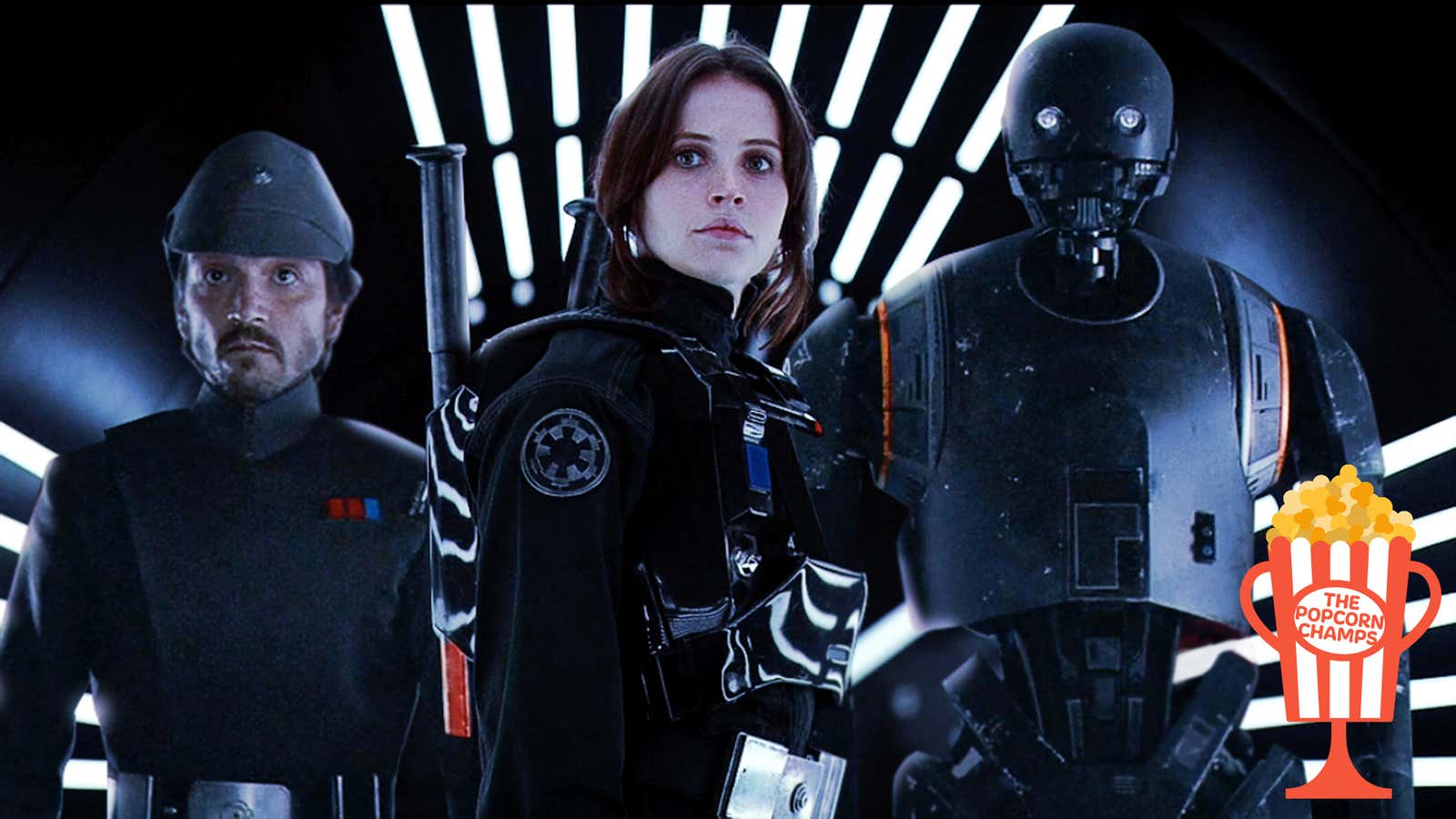

The cast is great, too. It’s a little weird that Disney followed The Force Awakens with another Star Wars story built around a tiny, young white British lady. But Felicity Jones, the star of Rogue One, had already been nominated for an Oscar, and she possesses the gravity and toughness that the traumatized war-orphan character demanded. Rogue One surrounds Jones with some impressive actors from across the global cinematic landscape: Mendelsohn, Whitaker, Diego Luna, Riz Ahmed, Mads Mikkelsen, Jiang Wen. These are all interesting actors with great, expressive faces. All of them have presence, and all of them make the most of their limited screen time.

For my money, the best member of that supporting cast is also the best straight-up movie star on the planet. Donnie Yen doesn’t get a ton of screen time in Rogue One, but he manages to show both his warm, graceful charm and his near-impossible physical fluidity. It’s wild that Yen, one of the biggest names in Hong Kong cinema, has never really gotten a shot in Hollywood. Yen grew up partly in America and speaks fluent English, and Rogue One remains his only strong star turn in a Hollywood movie. Yen only gets a couple of chances to go all Ip Man on Stormtroopers in Rogue One, but those moments are glorious.

The technical people involved in Rogue One all do amazing work, too. Rather than filming the entire thing on soundstages, Gareth Edwards shot as much of Rogue One as possible in stunning natural locations like Iceland, Jordan, and the Maldives. Where The Force Awakens presented a series of planets that looked just like previously established Star Wars worlds, Rogue One has entire new environments: a ringed rocky wasteland, a beachfront paradise, a Blade Runner-in-the-desert sacred city. Rogue One functions fully within the long-established Star Wars visual scheme, and it includes constant references to the aesthetics of the 1977 original. But it has fun coloring in those lines. Even as it digs into the nostalgic spectacle of the X-wing dogfight, it makes sure that happens in a landscape where we haven’t already seen all this go down before.

Rogue One also presents the oddly satisfying spectacle of familiar characters and types doing things we haven’t seen before. The final scene of Darth Vader physically mowing through rebel troops like a juggernaut is the most obvious holy-shit moment in the movie, but there are others. I love the idea that the Death Star’s weak spot isn’t just a design flaw; it’s a tiny piece of sabotage from an Oppenheimer-type scientist trying to get his quiet revenge on the murderous regime that’s conscripted him, and I love the idea that most of the Rebellion leaders are bickering do-nothings worried to confront the evil that’s right in front of them—galactic versions of centrist Democrats. I don’t love seeing the reanimated CGI face of Peter Cushing, an actor who died in 1994; it gives the weird sense that Disney considers the actual death of a human actor to be an inconvenience to be brushed aside. But I do love the idea that all the Empire leaders are like corporate suits jockeying for power and taking credit for each other’s ideas.

Rogue One didn’t have to exist; it’s a side story in a greater narrative, a digressive little chapter. The nods to other Star Wars movies are fun, but they’re not necessary. Ultimately, Rogue One has to function on its own—as its own story, with its own heroes and villains and stakes, and it succeeds on those levels. The characters never become anything more than types, but in that, Rogue One exists within a grand war-movie tradition: We meet the colorful ragtag members of the team, we get to like them without knowing them too well, and then we watch most of them die heroically. It’s the Dirty Dozen model, and there’s a reason why this particular set of clichés works so well.

The only real character arc in Rogue One belongs to Jones’ Jyn Erso, an embittered survivor who has to learn the worthiness of sacrifice. Jones does her best with it, but the character itself is hollow and one-note, and the film never earns its brief big-speech moment. But the movie does function as an ensemble piece, with all the different characters finding their own reasons to sacrifice themselves. Luna’s Cassian Andor, for instance, is a spy who’s rationalized his way into becoming a liar and a murderer, doing Battle Of Algiers shit for the greater good. Ahmed’s Imperial-defector pilot Bodhi Rook has fallen under the spell of a charismatic moralist, and he wants to make up for the bad things that he’s done. Yen’s Chirrut Îmwe is a religious-fanatic true believer, while his friend, Wen’s Baze Malbus, is a hardened cynic, but they’ve got a battlefield bond that clearly goes back a long way. All these pieces matter.

There’s not a ton of comic relief in Rogue One, but the movie does have Alan Tudyk as the reprogrammed Imperial droid K-2SO, a strange combination of C-3PO and the T-800 from Terminator 2. K-2SO is prim and socially maladjusted, but he’ll also smash someone on the head if the moment calls for it. K-2SO doesn’t want to kill and hack one of his own kind, but he’s ready to do it. When K-2SO suddenly turns into Kane in an early-’00s Royal Rumble, chokeslamming stormtroopers all over the place, it’s a primally thrilling moment. When he dies in battle, it actually stings.

Ultimately, everyone dies in the battle, a storytelling decision that seemed audacious at the time. Movies about heroic sacrifice are nothing new, but over the past decade and a half, Disney franchise storytelling has conditioned us to expect each movie to build to the next. Rogue One doesn’t play that. These characters are pawns in a bigger game, and they all lay down their lives to do something important. When Jyn Erso and Cassian Andor are consumed in a pillar of light, it’s an impressive sight.

Of course, in blockbuster films, no one ever really dies. Right now, Diego Luna is filming a Disney+ series about Cassian Andor. In real life, though, people die, and one death gave Rogue One an unintended emotional punch. The film’s final shot is an uncanny CGI recreation of the face of teenage Carrie Fisher, as we remember her from the beginning of Star Wars. Fisher died 11 days after Rogue One opened, and for anyone who saw the film after Fisher’s death, the image of Princess Leia getting ready to carry out a revolution was oddly moving.

Rogue One seemed like a movie that didn’t need a sequel, one that wrapped up all its loose ends by the time the credits rolled. That’s not how franchises function, though. Nobody really needs to know anything about Cassian Andor’s life pre-Rogue One, but nobody really needed Rogue One, either, and Disney still found a way to make it happen. Maybe the corporate interference helped Rogue One click, or maybe it just turned a potentially great movie into a merely good one. But the Disney corporate machine was absolutely humming in 2016. Rogue One didn’t tower over all the other movies at that year’s box office, as The Force Awakens did the year before. But the only movies that came close to Rogue One’s totals—Finding Dory and Captain America: Civil War—were Disney properties, too. That company knows what people want.

These days, Rogue One lives on as a clear inspiration for all the extra Star Wars stuff that Disney continues to crank out. Over the past two years, The Mandalorian has shown, once again, that the whole Star Wars milieu can serve as a great setting for mass-appeal stories that only occasionally overlap with the whole Skywalker saga. As the movies have fallen messily apart, that storytelling style looks like the way forward for Star Wars—and maybe for huge and dominant franchises in general. We’ll see.

The contender: Zootopia, another Disney product, is one more piece of mainstream entertainment that’s smarter and more entertaining than it had to be. The idea of a city full of anthropomorphic animals is fun enough; Disney competitors Illumination did something similar with The Secret Life Of Pets, an even bigger 2016 hit. But Zootopia uses that setting for a noir detective story with a ton of slick little twists and a rich sense of visual imagination. I don’t know what I expected Zootopia to be, but I didn’t expect that.

Next time: Rian Johnson’s Star Wars: Episode VIII—The Last Jedi pushes against the nostalgia of The Force Awakens, which makes for a cool and unpredictable movie and which then causes a whole conglomerate to grovel for forgiveness.