When Moonlight pulled a big upset and won the Best Picture Oscar a year ago, it felt like a monumental occasion—and not just because of the snafu that resulted in a different film briefly enjoying the honor. Yes, the Academy bestowed best-movie-of-the-year status on an actual, legitimate contender for the best movie of the year. That hasn’t happened too often over the 90 years the organization has been handing out awards. In fact, the Oscars often don’t just whiff on what deserves to win; they also frequently fail to even nominate the best movies, leaving some essential classic in the making out of the running entirely.

With this year’s ceremony just days away, The A.V. Club has singled out 90 important, terrific, even canonical movies that weren’t nominated—one for every Best Picture lineup going back to the beginning. We’ve followed the Academy’s rules about what qualifies, which mainly means only selecting movies that opened in the United States during each year’s eligibility window, including foreign-language films that took a minute to make it to America. Most years, you could program a film festival from the list of viable alternative candidates and snubbed triumphs, so consider this a kind of parallel cinematic history—a much different window into a century of movies than the one the Academy has opened. Hindsight is, of course, 20/20, but you’d have to be legally blind to ignore most of these films, especially given what often made the cut instead.

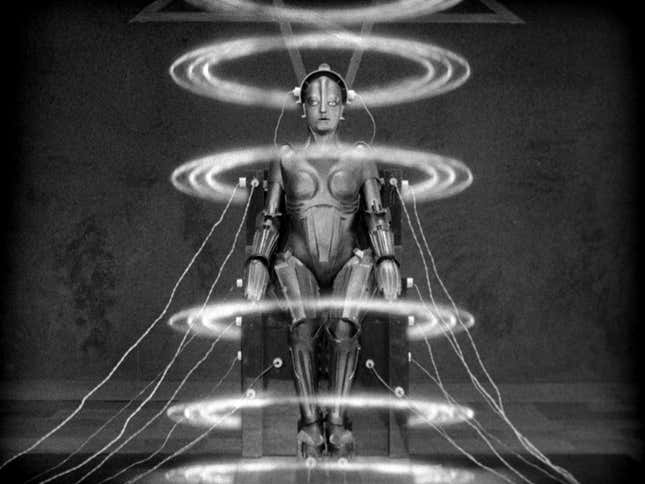

1927/28: Metropolis

The actual nominees: (Outstanding picture) 7th Heaven, The Racket, Wings; (unique and artistic picture) Chang: A Drama Of The Wilderness, The Crowd, Sunrise

Although the first-ever Academy Awards—which covered two years, with what is now Best Picture split into two different categories—recognized some of the era’s greatest achievements (including King Vidor’s The Crowd and F.W. Murnau’s sublime Sunrise), they also kicked off the Oscars’ history of glaring omissions by snubbing this massively influential classic of dystopian sci-fi. In a futuristic city in the year 2026, an industrialist strikes a devil’s bargain to manipulate the underclass (who literally live underground) by replacing a saintly preacher with a robotic femme fatale built by a bitter scientist. Metropolis may be the least challenging or ambiguous of the great German director Fritz Lang’s major films, but its breathtaking and stark vision of the future is the stuff big-screen spectacle is made of. [Ignatiy Vishnevetsky]

1928/29: The Passion Of Joan Of Arc

The actual nominees: Alibi; The Broadway Melody; Hollywood Revue; In Old Arizona; The Patriot

And to think Academy voters are supposed to be suckers for a star-making turn. A veteran French stage actress who was better known for light comedy fare, Renée Falconetti gave what may be the single greatest performance in the history of film in Carl Theodor Dreyer’s atomically powerful The Passion Of Joan Of Arc. Like Metropolis, it’s a reminder that silent film reached the peak of its artistic and technical ambition right as it went extinct. But although Passion was a critical success even in the United States (“makes worthy pictures of the past look like tinsel shams,” wrote The New York Times), the Academy was too busy rewarding clumsy early musicals and part-talkies to notice. [Ignatiy Vishnevetsky]

1929/30: City Girl

The actual nominees: All Quiet On The Western Front; The Big House; Disraeli; The Divorcee; The Love Parade

F.W. Murnau’s Sunrise is rightly hailed as one of the peerless masterpieces from the final years of Hollywood’s silent era. But just as much attention should be paid to City Girl, released the year before the director died. Like Sunrise, this story of young lovers in crisis—torn apart by the unexpected harshness of life working on a farm—is at once primal and lyrical, and dresses up a simple plot with gasp-inducing imagery. [Noel Murray]

1930/31: City Lights

The actual nominees: Cimarron; East Lynne; The Front Page; Skippy; Trader Horn

Charles Chaplin, then the most popular entertainer in the world, created one of the era’s most transcendent entertainments in this poignant Depression-era fantasia, in which the writer-director’s mustachioed Tramp character falls in love with a blind flower seller who has mistaken him for a millionaire, building to one of the most touching endings in film. Perhaps the lack of spoken dialogue killed the film’s chances with the early Oscars’ pro-talkie voters; the similarly iconic Modern Times didn’t pick up any nominations either when it appeared in 1936. [Ignatiy Vishnevetsky]

1931/32: Scarface

The actual nominees: Arrowsmith; Bad Girl; The Champ; Five Star Final; Grand Hotel; One Hour With You; Shanghai Express; The Smiling Lieutenant

The first stone-cold masterpiece of director Howard Hawks’ career (but not the last one on this list) was the movie every other gangster flick was measured against until The Godfather dethroned it 40 years later, and remains one of the most perfect examples of the crime film as a work of art. Inspired by the exploits of Al Capone, Scarface renders the rise and fall of a psychopathic Chicago gangster (Paul Muni) in exhilarating terms—a mix of violence, wit, expressionism, dark comedy, and technical brio. [Ignatiy Vishnevetsky]

1932/33: King Kong

The actual nominees: 42nd Street; A Farewell To Arms; Cavalcade; I Am A Fugitive From A Chain Gang; Lady For A Day; Little Women; The Private Life Of Henry VIII; She Done Him Wrong; Smilin’ Through; State Fair

The Academy’s habit of excluding massive popcorn entertainments from the Best Picture lineup goes all the way back to the granddaddy of them all, the true bellwether of special-effects blockbusters. Shut out at the Oscars (many of the technical categories it might have dominated hadn’t yet been introduced), King Kong had to settle for mountains of money, rave reviews, and the enchantment of adolescents of all ages. Nearly a century later, its state-of-the-art spectacle—the awe and wonder of a primordial beast, scaling a skyscraper in search of his beauty—remains a model for how to conquer imaginations. [A.A. Dowd]

1934: The Scarlet Empress

The actual nominees: The Barretts Of Wimpole Street; Cleopatra; Flirtation Walk; The Gay Divorcee; Here Comes The Navy; The House Of Rothschild; Imitation Of Life; It Happened One Night; One Night Of Love; The Thin Man; Viva Villa!; The White Parade

Lavish biopics of European royalty have been considered Oscar bait since the advent of the talkie, but there’s nothing respectable about Josef Von Sternberg’s delirious reimagining of the life of Catherine The Great—perhaps the most opulently grotesque film of the 1930s. The director’s muse, Marlene Dietrich, stars as the Prussian-born Russian monarch, leading a cast in which everyone seems to be speaking with a different accent. Amid the dripping candles and contorted gargoyles, their voices mingle into a scandalous texture of sadism, eroticism, and dark humor. Sternberg joked that his movies could be projected upside down, but The Scarlet Empress is more than an exercise in decadent overkill; its gutsy subject is the relationship of sex, repression, and politics. [Ignatiy Vishnevetsky]

1935: Bride Of Frankenstein

The actual nominees: Alice Adams; Broadway Melody Of 1936; Captain Blood; David Copperfield; The Informer; The Lives Of A Bengal Lancer; A Midsummer Night’s Dream; Les Misérables; Mutiny On The Bounty; Naughty Marietta; Ruggles Of Red Gap; Top Hat

While a generation of filmgoers rediscovered its brilliance thanks to 1998’s Gods And Monsters, Bride Of Frankenstein stood as a classic for 60 years. The rare critically acclaimed horror film that’s a sequel that improves on the original, James Whale’s gothic, campy marvel is also one of the most forward-thinking major releases of its time—a monster of an achievement for any era, even if the Academy didn’t notice. [Alex McLevy]

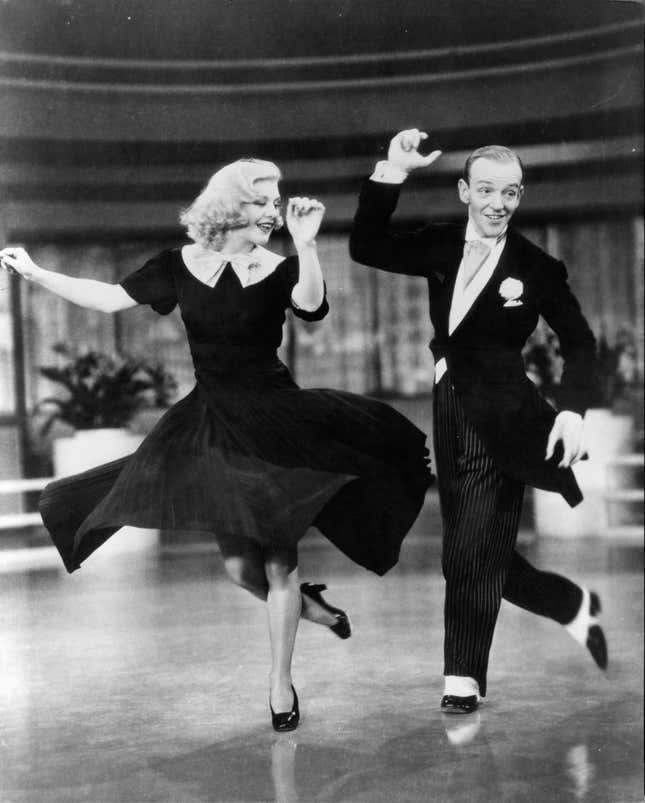

1936: Swing Time

The actual nominees: Anthony Adverse; Dodsworth; The Great Ziegfeld; Libeled Lady; Mr. Deeds Goes To Town; Romeo And Juliet; San Francisco; The Story Of Louis Pasteur; A Tale Of Two Cities; Three Smart Girls

In the finest of the Astaire-Rogers musicals, Fred and Ginger go a little less posh, a little more Depression-era to play, respectively, a humble dance instructor and a lucky gambler. Some of the most amazing songs (“A Fine Romance,” “The Way You Look Tonight”) don’t have any dancing at all, just a lovely wintry setting and two performers expert at luring the camera into capturing every beat of their romance. It may lack the flashy glamour of Top Hat (and “Bojangles Of Harlem” is problematic, though Astaire meant it as a tribute), but there’s no better showcase for the chemistry and the heart that this pair brought to the screen. [Gwen Ihnat]

1937: Make Way For Tomorrow

The actual nominees: The Awful Truth; Captain Courageous; Dead End; The Good Earth; In Old Chicago; The Life Of Emile Zola; Lost Horizon; One Hundred Men And A Girl; Stage Door; A Star Is Born

Director Leo McCarey’s Depression-era melodrama about an aged couple who can’t afford to live together anymore is devastatingly sad and incredibly well-observed, paying attention not just to the economic conditions tearing a family apart but also to the generational divides that shut the elderly out of society. It should be required viewing for any politician who considers slashing Social Security. [Noel Murray]

1938: Bringing Up Baby

The actual nominees: The Adventures Of Robin Hood; Alexander’s Ragtime Band; Boys Town; The Citadel; Four Daughters; Grand Illusion; Jezebel; Pygmalion; Test Pilot; You Can’t Take It With You

Howard Hawks’ screwball comedy tanked so hard at the box office, despite the star power of Katharine Hepburn and Cary Grant, that RKO preemptively fired Hawks from directing 1939’s Gunga Din and tried to demote Hepburn to B-movies. Unsurprisingly, the Academy bestowed zero nominations on it come Oscar time, but the zippy energy, witty dialogue, and chemistry between the leads eventually turned Bringing Up Baby into a beloved classic. [Kyle Ryan]

1939: Only Angels Have Wings

The actual nominees: Dark Victory; Gone With The Wind; Goodbye Mr. Chips; Love Affair; Mr. Smith Goes To Washington; Ninotchka; Of Mice And Men; Stagecoach; The Wizard Of Oz; Wuthering Heights

No shortage of candidates here, as 1939 has long been considered the annus mirabilis of Hollywood’s golden age. The most egregiously overlooked, however, is Howard Hawks’ paean to professionalism in the face of tragedy, set among a group of daredevil pilots (headed by Cary Grant) who deliver airmail in a fictional South American country, no matter how treacherous the conditions. Alternately hilarious and heartbreaking, it’s as breathlessly paced as many of Hawks’ classic comedies, and features a typically contentious romance (Jean Arthur co-stars), but also makes a poignant case for unconventional grieving. [Mike D’Angelo]

1940: The Shop Around The Corner

The actual nominees: All This, And Heaven Too; Foreign Correspondent; Kitty Foyle; The Grapes Of Wrath; The Great Dictator; The Letter; The Long Voyage Home; Our Town; The Philadelphia Story; Rebecca

During his storied career, Ernst Lubitsch had three films nominated for Best Picture, but it’s telling that the Academy overlooked his most brilliant and enduring picture. This comedy of manners oozes with Lubitsch’s trademark wit and charm, anchored by the twin performances of Jimmy Stewart and Margaret Sullavan as competing sales clerks who also happen to be lovingly (and unknowingly) corresponding with one another. The Shop Around The Corner is one of the bedrocks of romantic comedies, its influence sewn into the seams of every Must Love Dogs or Sleepless In Seattle—or most notably, its direct descendent, the not-so-modern-anymore remake You’ve Got Mail. [Leonardo Adrian Garcia]

1941: The Lady Eve

The actual nominees: Blossoms In The Dust; Citizen Kane; Here Comes Mr. Jordan; Hold Back The Dawn; How Green Was My Valley; The Little Foxes; The Maltese Falcon; One Foot In Heaven; Sergeant York; Suspicion

Only one comedy made it onto the Academy’s list of Best Picture nominees for 1941, a slate otherwise dominated by star-driven biographical dramas. But—with apologies to the cast and crew of Here Comes Mr. Jordan—the most sophisticated comedy of the year wasn’t made by Columbia. That honor should have gone to Paramount release The Lady Eve, Preston Sturges’ sparkling, romantic sleight-of-hand trick of a film starring Barbara Stanwyck as whip-smart con artist Jean Harrington and Henry Fonda as googly-eyed brewery heir Charles Pike, the fly who ends up catching the spider and one of cinema’s all-time greatest dopes. [Katie Rife]

1942: To Be Or Not To Be

The actual nominees: 49th Parallel; Kings Row; The Magnificent Ambersons; Mrs. Miniver; The Pied Piper; The Pride Of The Yankees; Random Harvest; The Talk Of The Town; Wake Island; Yankee Doodle Dandy

Once more, the court jester can say that which no one else is allowed. Ernst Lubitsch’s comedy of errors about a theater troupe in Warsaw standing up to the Nazis was frowned upon in initial release—how could they mock this real-world fight we’re in?—but it’s a sly masterstroke, wittily using artifice to uproot toxic ideology. Plus, it gave Jack Benny the role of his life, even if the Academy that year was more inspired by the feel-good heroics of James Cagney in Yankee Doodle Dandy. [Alex McLevy]

1943: The Leopard Man

The actual nominees: Casablanca; For Whom The Bell Tolls; Heaven Can Wait; In Which We Serve; Madame Curie; The Human Comedy; The More The Merrier; The Ox-Bow Incident; The Song Of Bernadette; Watch On The Rhine

The Academy is still working through its anti-genre film bias in 2018, so a Best Picture nomination for any of the artistically refined B-chillers Val Lewton and Jacques Tourneur made for RKO would certainly have been too much to ask in 1943. But the fact remains that The Leopard Man, one of two films Tourneur directed that year, was ahead of its time both in style and content. An episodic serial-killer mystery produced decades before the term was even coined, the film finds primal terror in the mere suggestion of a man who kills like a beast, a thematic tension between humanity’s godly and animal natures that echoes across the decades in films like Manhunter and Seven. [Katie Rife]

1944: Meet Me In St. Louis

The actual nominees: Double Indemnity; Gaslight; Going My Way; Since You Went Away; Wilson

A huge commercial and critical success upon release, Meet Me In St. Louis was nevertheless shut out of all major Oscar categories. Vincente Minnelli’s affecting portrait of a year in the life of a large St. Louis family around the 1904 World’s Fair produced iconic songs (“Have Yourself A Merry Little Christmas,” “The Trolley Song”) and great performances from an ensemble that included a never-better Judy Garland and youngster Margaret O’Brien, who did win a juvenile Oscar. [Kyle Ryan]

1945: Brief Encounter

The actual nominees: Anchors Aweigh; The Bells Of St. Mary’s; The Lost Weekend; Mildred Pierce; Spellbound

David Lean would go on to direct two Best Picture winners, with The Bridge On The River Kwai and (especially) Lawrence Of Arabia making his name synonymous with “sweeping epic.” Equally magnificent, though, is this intimate two-hander, written by Noel Coward and set largely in railway stations and restaurants. The story is simplicity itself: Happily married woman (Celia Johnson) meets attractive single man (Trevor Howard) and they fall passionately, miserably in love. Their weekly meetings, during which they struggle to maintain the fiction that they’re just friends, evolve into one of the great platonic romances in cinema history. [Mike D’Angelo]

1946: Children Of Paradise

The actual nominees: The Best Years Of Our Lives; Henry V; It’s A Wonderful Life; The Razor’s Edge; The Yearling

Apart from being French, Marcel Carné’s three-hour, two-part extravaganza seems tailor-made for Oscar glory. In addition to being long, it’s a period piece (set in the early 19th century) about the entertainment world (Parisian theater), made under incredibly trying circumstances (say, aren’t those Nazi uniforms on every corner?). Icing on the cake: Its discursive tale of a courtesan (Arletty) pursued over the years by four different men—including, just to prove that it’s French, the city’s most beloved mime—is so deeply moving that François Truffaut once said he’d trade all of his movies just to have made this one. [Mike D’Angelo]

1947: Beauty And The Beast

The actual nominees: The Bishop’s Wife; Crossfire; Gentleman’s Agreement; Great Expectations; Miracle On 34th Street

The Academy had no separate category to recognize foreign-language films until 1956, so it’s no surprise that Jean Cocteau’s visually striking magical romance Beauty And The Beast went unrecognized. Cocteau, who cut his teeth with such avant-garde fare as The Blood Of A Poet, elevates the classic tale of tormented Belle and cursed Beast by bathing every frame with Freudian imagery or otherworldly opulence. To quote the late Roger Ebert, “Blood Of A Poet was an art film made by a poet,” whereas, “Beauty And The Beast was a poetic film made by an artist.” [Leonardo Adrian Garcia]

1948: Day Of Wrath

The actual nominees: Hamlet; Johnny Belinda; The Red Shoes; The Snake Pit; The Treasure Of The Sierra Madre

Carl Theodor Dreyer’s other masterpiece about women being burned at the stake shares The Passion Of Joan Of Arc’s stark vision of the past, but otherwise shows that the Danish master was as much of an original artist in the sound era as he had been in silent films. Made in 1943 under Nazi occupation and released in the United States five years later, Dreyer’s drama about 17th-century witch hunts is more than an allegory for totalitarian paranoia. It’s the anti-Crucible—an ambiguous, powerfully eerie portrait of a society in which everyone believes in supernatural evil. [Ignatiy Vishnevetsky]

1949: Bicycle Thieves

The actual nominees: All The King’s Men; A Letter To Three Wives; Battleground; The Heiress; Twelve O’Clock High

From its cast of non-professional actors to its verité shooting style to its focus on the hard realities of unglamorous working-class lives, this neorealist milestone is basically the antithesis of the kind of extravagant productions the Oscars were largely celebrating mid-century. But even the Academy couldn’t entirely ignore Vittorio De Sica’s simple, quietly devastating tale of a father and son searching for the stolen bike on which their very survival depends. A screenplay nomination and an honorary Oscar presaged the film’s rapidly growing esteem, which culminated in Bicycle Thieves topping the very first Sight & Sound poll of the best movies ever made, just four years after its initial release in Italy. [A.A. Dowd]

1950: The Third Man

The actual nominees: All About Eve; Born Yesterday; Father Of The Bride; King Solomon’s Mines; Sunset Boulevard

Routinely on critics’ lists of the best films ever made, Carol Reed’s suspense classic wasn’t nominated for Best Picture—a shocking snub, even in an admittedly great year for movies. The Third Man is steeped in the influence of Orson Welles’ intoxicating Citizen Kane brand of noir, and Welles himself showboats as the mysterious and hopelessly corrupt Harry Lime. Stark postwar Vienna, the Swiss cuckoo-clock speech in the Ferris wheel, the omnipresent zither: A movie that’s still such an indispensable part of the overall fabric of cinema deserved to win the whole thing. [Gwen Ihnat]

1951: Ace In The Hole

The actual nominees: An American In Paris; Decision Before Dawn; Quo Vadis; A Place In The Sun; A Streetcar Named Desire

Originally called The Big Carnival, Billy Wilder’s searing indictment of American journalism holds up as the newspaper-business equivalent of Network, a disillusioned cry of despair against a corrupted and capitalistic press. Kirk Douglas plays a disreputable reporter who uses a human tragedy for profit, and the resulting story about how the news manipulates public sentiment inveighs against the worst of human impulses in a manner more timely than ever. You can see why the Oscars would politely overlook it—the thing’s bleak as hell. [Alex McLevy]

1952: Singin’ In The Rain

The actual nominees: The Greatest Show On Earth; High Noon; Ivanhoe; Moulin Rouge; The Quiet Man

For proof that the Oscars are best viewed as a snapshot of the year in film and not an arbiter of lasting cinematic greatness, see The Greatest Show On Earth, one of the worst movies to ever win Best Picture. See also: The fact that Cecille B. DeMille’s three-ring spectacle didn’t have to compete against Gene Kelly hoofing his way through soundstage puddles. Shut out of the race for the top prize at the 25th Academy Awards, Singin’ In The Rain at least earned nods for Lennie Hayton’s sprightly score and Jean Hagen’s heel turn as Lina “I cayn stan’ ’im” Lamont. Its easygoing blend of screwball romance, end-of-the-silent-age myth-making, and eye-dazzling choreography would only improve with age; a list of 1952’s best movies sans Singin’ In The Rain now looks as incongruous as Debbie Reynolds’ voice coming out of Hagen’s mouth. [Erik Adams]

1953: Pickup On South Street

The actual nominees: From Here To Eternity; Julius Caesar; The Robe; Roman Holiday; Shane

The five nominees for Best Picture of 1953 boast a decent variety of genres (romantic comedy, Western, biblical epic), but the category could have been even more eclectic with the addition of Samuel Fuller’s brisk, bold thriller. The story of a wiseass pickpocket who inadvertently lifts a much-desired piece of microfilm from a hard-luck dame garnered a single nomination for Thelma Ritter’s supporting role as an opportunistic informant, but Fuller’s technically dazzling and influential hybrid of noir and spy picture deserved more. [Jesse Hassenger]

1954: Rear Window

The actual nominees: The Caine Mutiny; The Country Girl; On The Waterfront;

Seven Brides For Seven Brothers; Three Coins In The Fountain

On its face, this Hitchcock thriller is a straightforward murder-mystery, with Jimmy Stewart’s photojournalist eyeing his increasingly suspicious neighbor through the window overlooking their communal backyard. But Rear Window is more than a mere whodunit. Its close look at voyeurism and gender politics would assure it survived far beyond its Best Picture slight and into the history of the medium. [Laura Adamczyk]

1955: All That Heaven Allows

The actual nominees: Love Is A Many-Splendored Thing; Marty; Mister Roberts; Picnic; The Rose Tattoo

The most Sirkian of all the Douglas Sirk melodramas, All That Heaven Allows reunites Magnificent Obsession stars Jane Wyman and Rock Hudson for a then-controversial May-December romance, rocking the country-club set and inflexible, ungrateful grown children of Wyman’s heroine. Augmented by pastel-tinged forest-postcard imagery, Heaven should have been the gem of a rather weak lineup; it could have easily booted Marty, Love Is A Many-Splendored Thing, Picnic, or The Rose Tattoo. (We’ll keep Mister Roberts.) [Gwen Ihnat]

1956: Seven Samurai

The actual nominees: Around The World In 80 Days; Friendly Persuasion; Giant; The King And I; The Ten Commandments

Was it just subtitles that prevented Seven Samurai from storming the 29th Academy Awards? In an era of epics, few could match the grandeur of Akira Kurosawa’s endlessly imitated, at least twice remade spectacular, in which seven wandering swordsmen (among them the director’s volatile muse, Toshirô Mifune) vow to protect a village from an army of bandits—a likely suicide mission that ends with a rain-soaked battle royale for the ages. Nominated for only its costumes and art design, Seven Samurai lives on in the DNA of countless award-winning ancestors, from Star Wars to Lord Of The Rings to just about any portrait, East or West in origin, of noble warriors staring down impossible odds. [A.A. Dowd]

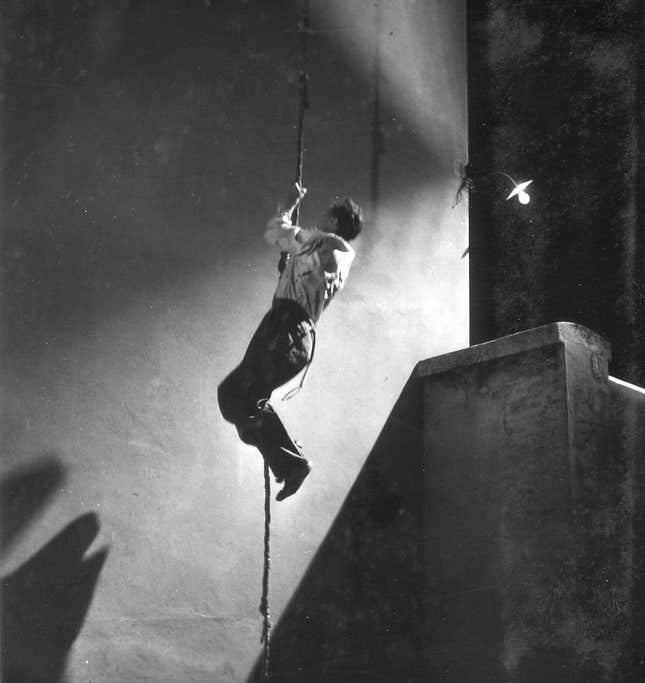

1957: A Man Escaped

The actual nominees: 12 Angry Men; The Bridge On The River Kwai; Peyton Place; Sayonara; Witness For The Prosecution

Considering that A Man Escaped was a success with both critics and awards-giving bodies (including the BAFTAs, which nominated it for the equivalent of Best Picture), one can’t help but ask: Was it too much of an art film for Academy tastes or too much of a genre movie? The purest of all prison-break films, Robert Bresson’s masterpiece recreates a real-life escape by a French Resistance member from a Gestapo prison in 1943, though it’s just as informed by the writer-director’s own experiences as a prisoner of war. The director’s singular, pointed minimalism elevates the escape into a spiritual experience—the dark night of the soul. [Ignatiy Vishnevetsky]

1958: Vertigo

The actual nominees: Auntie Mame; Cat On A Hot Tin Roof; The Defiant Ones; Gigi; Separate Tables

Easy choice, since this is now widely considered one of the two or three greatest movies ever made. (It supplanted longtime champ Citizen Kane in the top spot of the most recent Sight & Sound poll.) One can only wonder what folks back then—and it wasn’t just Oscar voters, by any means—were thinking. Could they not see past the genre mechanics to Hitchcock’s devastating self-portrait, in which Jimmy Stewart’s retired detective becomes so obsessed with a dead woman (Kim Novak) that he meticulously recreates another woman in her image? Did they not have ears with which to hear Bernard Herrmann’s swoon-worthy score? Truly mystifying. [Mike D’Angelo]

1959: Rio Bravo

The actual nominees: Anatomy Of A Murder; Ben-Hur; Room At The Top; The Diary Of Anne Frank; The Nun’s Story

A mighty year for film, 1959 saw many of Hollywood’s old masters at the peak of their powers. Billy Wilder’s Some Like It Hot and Alfred Hitchcock’s North By Northwest also went unnominated, but our heart belongs to the greatest of all hangout movies. A frontier sheriff (John Wayne) guards a murderer with the help of an old coot (Walter Brennan), an alcoholic (Dean Martin), a young gun (Ricky Nelson), and a brassy gambler (Angie Dickinson), waiting for the inevitable moment when the prisoner’s compadres will try to break him out. The pace may be leisurely, but Rio Bravo is a marvel of construction—the magnificent bottle episode of director Howard Hawks’ career and the perfect summation of his fascinations and themes. [Ignatiy Vishnevetsky]

1960: Psycho

The actual nominees: The Alamo; The Apartment; Elmer Gantry; Sons And Lovers; The Sundowners

We could fill a quarter of this list with Alfred Hitchcock movies, given how surprisingly few of the master’s expert suspense contraptions made the Best Picture cut. But Psycho’s wrongheaded exclusion isn’t shocking, exactly. After this peerless, obscene prank of a thriller, nothing could be trusted: not your shower, not the aw-shucks boy next door, not even the safe security that a movie’s apparent protagonist would survive past the half-hour mark. Psycho’s monster success did end up securing it a few nominations (including Hitch’s fifth and final Best Director nod), but Picture was apparently a bridge too far for a low-budget proto slasher that gleefully broke Hollywood’s most sacred rules. [A.A. Dowd]

1961: L’Avventura

The actual nominees: Fanny; Judgment At Nuremberg; The Guns Of Navarone; The Hustler; West Side Story

As much so as Psycho, this trailblazing anti-drama announced that all bets were off. Suddenly, you could set up a mystery—the disappearance of a young socialite during a weekend boating trip—and just never resolve it. But L’Avventura, the first in Michelangelo Antonioni’s unofficial trilogy on the discontent of the leisure class, didn’t just throw out the narrative playbook. It also changed how art movies looked and moved, helping popularize long-take languor and the privileging of mood over plot. Too radical for some, the film premiered to boos at Cannes. What chance did it ever have with the conservative squares of the Academy? [A.A. Dowd]

1962: Cléo From 5 To 7

The actual nominees: Lawrence Of Arabia; The Longest Day; The Music Man; Mutiny On The Bounty; To Kill A Mockingbird

Somehow it’s taken until 2018 for the iconic French filmmaker Agnès Varda to earn her first-ever Oscar nomination—months after the Academy picked the 89-year-old to become the first woman to receive an honorary award for lifetime achievement in directing. Where were they in 1962? One of the director’s greatest achievements, the eloquent existentialist drama Cléo From 5 To 7 follows a twentysomething singer over the course of two hours, as she awaits the results of a biopsy to see if she has cancer. Although Varda’s career predated the French New Wave, Cléo plays like her take on the movement, whose modernism tended to rub the Academy the wrong way. [Ignatiy Vishnevetsky]

1963: 8 1/2

The actual nominees: America America; Cleopatra; How The West Was Won; Lilies Of The Field; Tom Jones

Federico Fellini’s 8 1/2 proves that the only thing better than finding inspiration in a new creative project is abandoning one that’s no longer inspiring. As with so many other snubbed greats, it was awarded the Best Foreign Film olive branch from the Academy—Fellini’s third such award—in part because of the way it transmutes Fellini’s personal creative journey into something universal and surreal. This is also, of course, the source of the film’s enduring power. [Clayton Purdom]

1964: The Umbrellas Of Cherbourg

The actual nominees: Becket; Dr. Strangelove, Or: How I Learned To Stop Worrying And Love The Bomb; Mary Poppins; My Fair Lady; Zorba The Greek

The Umbrellas Of Cherbourg’s Best Picture chances were as star-crossed as its doomed love affair. My Fair Lady already had the songs and the romance (and got the statuette) covered, Zorba The Greek got bittersweet among European working folk, and Dr. Strangelove depicted (in its cockeyed way) the tolls of war. The Palme D’Or winner and Best Foreign Film nominee couldn’t even claim to be the year’s only eye-candy musical in which rain gear factors prominently—not with Mary Poppins blowing in on the breeze from Old Blighty. Yet none of those nominees makes the stuff of everyday life feel so cinematic: The Umbrellas Of Cherbourg is a grounded drama that takes place in a pastel world where no one ever stops singing. It’s still one of the best examples of a movie unafraid to look and feel like a movie. [Erik Adams]

1965: Alphaville

The actual nominees: A Thousand Clowns; Darling; Doctor Zhivago; Ship Of Fools; The Sound Of Music

The Academy has, to put it mildly, been cold on Jean-Luc Godard, who, over the course of six decades and dozens of films, only received one award—an un-televised, honorary nod, given in 2010. (Godard did not show up to accept it.) They could’ve started, well, anytime would’ve been good, but Alphaville’s bold riff on sci-fi convention wrapped the auteur’s lightning-flash visual style into a dense meditation on technocratic control, modernist design, and the role of the artist in a technologically stifling society. As with his other 1965 classic, Pierrot Le Fou, it plays fast and loose with the energy of American pulp cinema. [Clayton Purdom]

1966: Blow-Up

The actual nominees: Alfie; A Man For All Seasons; The Russians Are Coming, The Russians Are Coming; The Sand Pebbles; Who’s Afraid Of Virginia Woolf?

It’s perhaps no surprise that the traditionally stodgy Academy passed on this hip Antonioni arthouse piece about a smug fashion photographer who witnesses a murder—or so he thinks. Though slowly paced and full of complex symbols and sexy Swinging London signifiers, Blow-Up explores heady ideas surrounding the nature of art and perception, resisting any single interpretation—often the mark of a great film, rarely the mark of an Oscar winner. [Laura Adamczyk]

1967: Persona

The actual nominees: Bonnie And Clyde; Doctor Dolittle; The Graduate; Guess Who’s Coming To Dinner; In The Heat Of The Night

One of the best films ever made by any critical metric, Ingmar Bergman’s funhouse-mirror psychoanalysis takes the form of a character study of an inexplicably mute actor (Liv Ullmann) and the young nurse (Bibi Andersson) assigned to her care. As their lives begin to blur together, Bergman pulls out game-changer after game-changer of cinematic innovation (including literal smoke and mirrors, at one point), all in an effort to push narrative and character to its limit. Critic Peter Cowie famously opined, “Everything one says about Persona may be contradicted; the opposite will also be true,” which helps to explain why the film continues to entrance and provoke viewers to this day. [Alex McLevy]

1968: 2001: A Space Odyssey

The actual nominees: Funny Girl; Oliver!; Rachel, Rachel; Romeo And Juliet; The Lion In Winter

Technically, structurally, philosophically: No matter what lens you view it through, 2001 remains among the most ambitious, awe-inspiring experiments ever bankrolled by a major studio. Stanley Kubrick’s unforgettable cosmic imagery rightly earned him a Best Director nomination, but his grand-scale marshaling of technology in the service of a singular, eon-spanning vision is just as much a feat of Best Picture’s purview, producing. The final trip into starchildhood has been wowing audiences for half a century, but to really have your mind blown, try to imagine someone preferring The Lion In Winter. [A.A. Dowd]

1969: The Wild Bunch

The actual nominees: Anne Of The Thousand Days; Butch Cassidy And The Sundance Kid; Hello Dolly!; Midnight Cowboy; Z

It seems the Academy didn’t really fall in love with Westerns until the genre had passed out of popular usage. The list of snubbed classics is immense—The Searchers, Rio Bravo, Red River, The Man Who Shot Liberty Valance, and Once Upon A Time In The West, just to name a few. There’s also, of course, Sam Peckinpah’s The Wild Bunch, which was only nominated for its script and score. (It was “good,” the Academy agreed, but not “Anne Of The Thousand Days good.”) A eulogy for the vulgar genre, The Wild Bunch put aging outlaws in a standoff with oblivion and changed the way violence was depicted in American film; many movies would follow in its bloody footsteps, but never with the understanding Peckinpah had of his characters. [Ignatiy Vishnevetsky]

1970: My Night At Maud’s

The actual nominees: Airport; Five Easy Pieces; Love Story; MASH; Patton

Dozens of droll romantic-intellectual gabfests have used My Night At Maud’s as a reference point, but none have matched the elegance and eloquence of Éric Rohmer’s hugely influential surprise hit—a shoestring-budget drama so good that the Academy nominated it two years in a row, first for Best Foreign Language Film, then for Best Original Screenplay. (Convoluted eligibility rules may have also played a role.) As in all of Rohmer’s best work, its true brilliance lies not in the dialogue, but in thoughtful, intimate composition; the French writer-director’s command of irony, body language, and deceptively simple forms was second to none. [Ignatiy Vishnevetsky]

1971: McCabe & Mrs. Miller

The actual nominees: A Clockwork Orange; Fiddler On The Roof; The French Connection; Nicholas And Alexandra; The Last Picture Show

Revisionist Westerns don’t get much more engrossing or poignant than McCabe & Mrs. Miller, and only this one has the songs of Leonard Cohen articulating what can’t be sifted from the customary Robert Altman conversation slurry. But tradition (“TRADITION!”) still held some cards at Oscar’s table in 1972: In the company of droogs, despondent Texan teens, and Popeye Doyle, John McCabe and Constance Miller still couldn’t get dealt in on the night’s big hand—not with deposed Russian royalty and singing Ukrainian peasants around. Even when Altman’s work was actually up for an Academy Award, he never won—a slight rectified with an honorary award in 2006, a half year before he died. [Erik Adams]

1972: The Discreet Charm Of The Bourgeoisie

The actual nominees: Cabaret; Deliverance; The Emigrants; The Godfather; Sounder

Luis Buñuel’s surrealist masterpiece won the Oscar for Best Foreign Language Film, but voters were clearly also willing to consider it for the major categories, since they nominated Buñuel and Jean-Claude Carrière for writing its screenplay. Hell, they even nominated a foreign film for Best Picture that year: Sweden’s The Emigrants, which had been up for Foreign Language Film the previous year, but lost. Presumably, a movie about a group of friends whose dinner plans keep being interrupted in ludicrous ways was just too weird for the Academy as a whole. But it remains a glorious, hilarious provocation. [Mike D’Angelo]

1973: Mean Streets

The actual nominees: American Graffiti; The Exorcist; Cries And Whispers; A Touch Of Class; The Sting

It’s a little silly to complain about Martin Scorsese not getting enough Oscar love, even if it took a few decades for the Italian-American master to finally move from bridesmaid to bride. All the same, Marty’s invitation to the Best Picture club should have arrived a little earlier, with a nomination for his run-riot, rock ’n’ roll breakthrough about a small-time thug (a young Harvey Keitel) and the hotheaded friend (an even younger Robert De Niro) who constantly yanks them both into trouble. Like De Niro slow-mo swaggering in to the Stones’ “Jumpin Jack Flash,” Mean Streets made for one hell of an entrance. [A.A. Dowd]

1974: A Woman Under The Influence

The actual nominees: Chinatown; The Godfather, Part II; Lenny; The Conversation; The Towering Inferno

Ungainly, star-packed, anonymously directed disaster movies were somehow considered a popular form of entertainment in the 1970s, fêted with mystifying Oscar nominations. Case in point: The Towering Inferno, an Irwin Allen production based on two different novels by three different authors (but mostly the success of The Poseidon Adventure) that competed for Best Picture against The Godfather Part II (which won), Chinatown, and The Conversation. It’s not like there wasn’t another American masterpiece on the Academy’s radar. Nominated for Best Director and Best Actress, A Woman Under The Influence was one of John Cassavetes’ greatest films—an extraordinary depiction of a fortysomething housewife (Gena Rowlands) slipping away from sanity, with a singular rhythm and structure that defies expectations. [Ignatiy Vishnevetsky]

1975: Cooley High

The actual nominees: Barry Lyndon; Dog Day Afternoon; Jaws; Nashville; One Flew Over The Cuckoo’s Nest

It’s hard to find much fault in the 1975 Best Picture lineup, possibly the strongest slate of contenders the Academy has ever arranged. So consider Cooley High more of an enthusiastic alternate. Tracking two Chicago teenagers (Glynn Turman and Lawrence Hilton-Jacobs) as they fast-talk their way in and out of trouble, this immensely entertaining coming-of-age comedy caught a lot of American Graffiti comparisons, thanks to a plot that plays like a nonstop party and a wall-to-wall FM soundtrack (made up mostly of Motown hits). But the joyous tomfoolery of Eric Monte’s autobiographical script eventually gives way to something more downbeat, even tragic: adulthood coming too soon, or not at all. [A.A. Dowd]

1976: Mikey And Nicky

The actual nominees: All The President’s Men; Bound For Glory; Network; Rocky; Taxi Driver

While her former comedy partner Mike Nichols was becoming the toast of Broadway and an Oscar favorite for his slick, sophisticated productions, writer-director Elaine May was heading in the opposite direction, actively trying to capture the wild inspiration of their improv days on film. Her ultra-low-key mob comedy Mikey And Nicky is radically shaggy, with Peter Falk and John Cassavetes playing pathetic thugs who spend more time grumbling than working. It’s one of the most unusual and original movies from an exciting era for American cinema. [Noel Murray]

1977: Suspiria

The actual nominees: Annie Hall; The Goodbye Girl; Julia; Star Wars; The Turning Point

Sure, it didn’t explode into a multi-billion-dollar global franchise, but in its way Suspiria is arguably almost as influential as Star Wars. Spend any amount of time watching contemporary horror movies and the chances are good that you’ll randomly wander into one that apes Suspiria’s jewel-tone lighting, dynamic prog-rock score, or both. Equally effective as a stylized exercise in baroque excess and a vividly nightmarish descent into Jungian archetype, Dario Argento’s occult fairy tale is now finally being recognized as the masterpiece that it is. [Katie Rife]

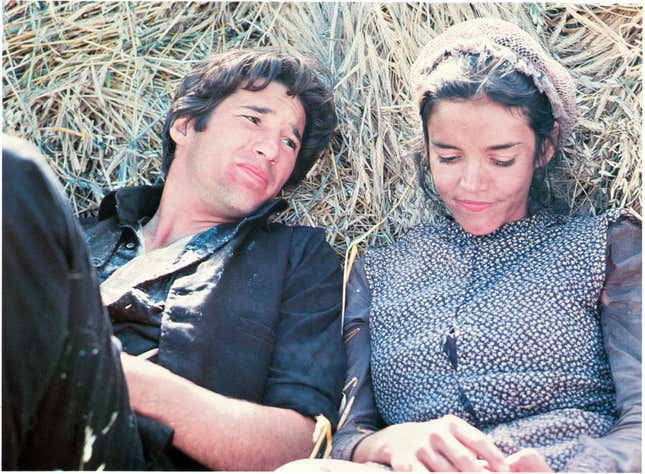

1978: Days Of Heaven

The actual nominees: Coming Home; The Deer Hunter; Heaven Can Wait; Midnight Express; An Unmarried Woman

Terrence Malick followed up his 1973 debut, Badlands, with an early pioneering of the picturesque visual grandeur that he would continue to perfect decades later in The Tree Of Life. Days Of Heaven follows two 1915 vagabonds (Brooke Adams and Richard Gere) through a love-triangle scheme involving a rich farmer (Sam Shepard) destined to end in tragedy. Malick took two years to edit the film, finally tying it all together with narration by husky-throated 14-going-on-74-year-old Linda Manz. Her voice lingers over impossibly beautiful images of fields of grain and locust swarms—all shot at the magic hour, a terminology wholly appropriate. At least the Academy recognized the film for that, handing Days Of Heaven the Best Cinematography Oscar. [Gwen Ihnat]

1979: Alien

The actual nominees: All That Jazz; Apocalypse Now; Breaking Away; Kramer Vs. Kramer; Norma Rae

Two years after the Academy overcame its bias against science fiction to nominate a certain popular space opera, along came another highly influential vision of rustic spaceships, paranoid androids, and extraterrestrial menace. But there’s little hope, new or otherwise, in Ridley Scott’s merciless, franchise-spawning monster movie, set within a leaky, foggy, futuristic Gothic manor floating silently across the inky vacuum of the cosmos. H.R. Giger’s acid-bleeding, oversized cockroach won Alien its only Oscar—an insufficient reward for such a perfect genre specimen. [A.A. Dowd]

1980: Airplane!

The actual nominees: Coal Miner’s Daughter; The Elephant Man; Ordinary People; Raging Bull; Tess

Surely the Oscars don’t always have to be so serious. Comedy seems to get nominated only under duress (or when it can pass as drama), so a gag-packed spoof of disaster movies (like the Best Picture-nominated Airport) never had a shot in hell. But the Zucker/Abrahams/Zucker classic Airplane! isn’t just hilarious; it’s revelatory, culminating years of Mel Brooks and Woody Allen parodies into a near-perfect joke machine. It’s also, in its omnivorous cinematic spoofery, a delightful expression of movie love. [Jesse Hassenger]

1981: Modern Romance

The actual nominees: Atlantic City; Chariots Of Fire; On Golden Pond; Raiders Of The Lost Ark; Reds

Now that Woody Allen’s classic movies have become toxically problematic, it’s time to revisit the work of another neurotic comedian-turned-filmmaker. Modern Romance is Albert Brooks’ masterpiece, weaving about a half-dozen brilliantly funny set pieces into the painfully realistic story of a pair of upper-middle-class Los Angelenos locked into a cycle of breaking up and making up—cripplingly heartbroken when they’re apart, but in a constant state of irritation when they’re together. [Noel Murray]

1982: Blade Runner

The actual nominees: E.T.: The Extra-Terrestrial; Gandhi; Missing; The Verdict; Tootsie

Ridley Scott’s future-noir was rightly nominated for its visuals, which certainly reflected the contemporary critical consensus that it’s more interesting as a work of design than cinema. (That 1982 critics were judging Scott’s original cut, leaden with Harrison Ford’s involuntary and audibly bored narration, certainly didn’t help.) But considering its remarkably lasting influence—on film, on music, on fashion, on all our most fantastically pessimistic dreams of what the future holds—Blade Runner looms far larger than its Oscar record would suggest, arguably even more significant than that year’s actual sci-fi Best Picture nominee, E.T. The Extra-Terrestrial. [Sean O’Neal]

1983: The King Of Comedy

The actual nominees: The Big Chill; The Dresser; The Right Stuff; Tender Mercies; Terms Of Endearment

A quick look at the 1983 nominees for Best Picture shows little room for The King Of Comedy, Martin Scorsese’s darkly comic examination of fan obsession. (A deranged fan of Jodie Foster, inspired by Scorsese’s Taxi Driver, had tried to kill President Reagan only three years earlier.) But The King Of Comedy remains one of Scorsese’s best, anchored by an incredible comeback performance by Jerry Lewis (as the Johnny Carson stand-in Jerry Langford) and the unhinged Robert De Niro as delusional fan Rupert Pupkin. [Kyle Ryan]

1984: Once Upon A Time In America

The actual nominees: Amadeus; The Killing Fields; A Passage To India; Places In The Heart; A Soldier’s Story

Piss-takes on the American dream are as old as movies about the mob (see: Scarface, an earlier entry on this list), but Sergio Leone’s gobsmacking, decades-spanning, realism-flouting 229-minute crime epic about Jewish gangsters in Manhattan takes it a few steps further: It’s a druggy haze, the mythic gangland as a dreamland of guilty imaginations. Here, we have to cut the Academy a little slack, as the drastically shortened and reordered version that first opened in American theaters made mince meat of Leone’s audaciously complex narrative. But it’s not like the flashback structure is the only thing Once Upon A Time In America has going for it. [Ignatiy Vishnevetsky]

1985: Brazil

The actual nominees: The Color Purple; Kiss Of The Spider Woman; Out Of Africa; Prizzi’s Honor; Witness

Walking a tonal tightrope between brief moments of human warmth and sheer, inescapable nihilism, Terry Gilliam’s vision of bureaucratic dystopia ably makes the case that well-meaning functionaries—like Michael Palin’s cheerful, family-loving torturer—can give a squad of fascist thugs a run for its money in the “banally evil” stakes. Gilliam’s skills as a visual artist are on full display here, creating a human ant farm of cramped spaces and lethal paperwork perfectly designed to make the fall of a typewriter key feel as brutal as a jackboot stamping on a human face. [William Hughes]

1986: Blue Velvet

The actual nominees: Children Of A Lesser God; Hannah And Her Sisters; The Mission; Platoon; A Room With A View

Blue Velvet is where David Lynch’s vision of small-town America as a Technicolor garden crawling with worms first emerged, springing fully formed from his subconscious like an Athena obsessed with Freudian surrealism and masochistic fantasy. Time has since vindicated Blue Velvet against the critics who condemned it as degenerate and depraved upon its initial release, but with Lynch stating in recent interviews that he’ll probably never make another feature film, the Academy’s window to redeem itself by finally giving him a Best Director Oscar appears to have permanently closed. [Katie Rife]

1987: RoboCop

The actual nominees: Broadcast News; Fatal Attraction; Hope And Glory; The Last Emperor; Moonstruck

Paul Verhoeven’s black comedy blow-’em-up took home the Oscar for Best Sound Editing, part of a string of technical nominations that, fittingly, failed to recognize the clever mind behind the machine. This corporate Frankenstein riff has more to offer than just a thrilling game of robot cops and robbers, however. It’s daring and bizarre, and its mordantly witty takes on American capitalism run amok still resonate (particularly in an age when every big company is vying to become our own Omni Consumer Products). RoboCop is that rare, subversive breed of film that completely transcends the silliness of its premise and the trappings of its genre, and it should have been recognized as such. [Sean O’Neal]

1988: Who Framed Roger Rabbit

The actual nominees: The Accidental Tourist; Dangerous Liaisons; Mississippi Burning; Rain Man; Working Girl

The Academy can usually be counted on to reward any contender that pays tribute to Hollywood. Was this Robert Zemeckis marvel, seamlessly combining vintage cartoon characters with a live-action noir set in 1947 Los Angeles, too cockeyed for the big prize, or did the presence of animation deter the fustier voters? Although its editing, cinematography, sound, visual effects, and art direction were all deemed nomination-worthy, the movie itself was not—a shame, because Roger Rabbit is more than the sum of its technical achievements, an accomplished piece of entertainment that kids its hometown with great affection. [Jesse Hassenger]

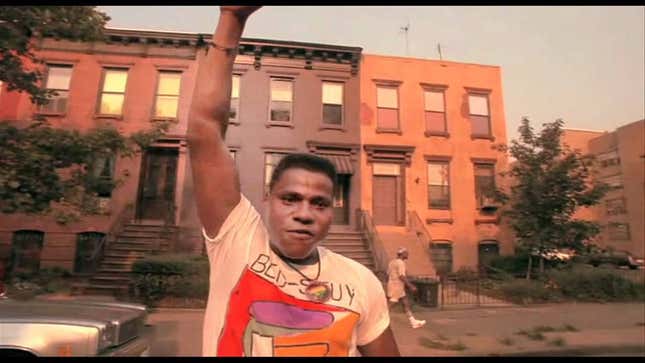

1989: Do The Right Thing

The actual nominees: Born On The Fourth Of July; Dead Poets Society; Driving Miss Daisy; Field Of Dreams; My Left Foot

There’s no better illustration of how out-of-touch the Academy can be than its failure to nominate Spike Lee’s electrifying ensemble drama. Set over the course of a single sweltering summer day in Bed-Stuy, Brooklyn, Do The Right Thing builds from scratch a whole neighborhood of competing personalities—a vivid, volatile microcosm of American life—and then watches with rage and sorrow as its racial conflicts heat from a simmer to a volcanic boil. It was easily the most debated, scrutinized, and ultimately acclaimed movie of 1989—a powder keg sensation all but ignored on Oscar night. The ultimate insult on top of injury? Best Picture went to Driving Miss Daisy instead. [A.A. Dowd]

1990: Edward Scissorhands

The actual nominees: Awakenings; Dances With Wolves; Ghost; The Godfather, Part III; Goodfellas

At the end of the 1980s, Tim Burton directed a blockbuster about a superhero for which he felt no particular affinity. As a follow-up, he realized an idea he’d been carrying around for years, a suburban Frankenstein story in which the creator is played by Burton’s childhood idol and his creation has the filmmaker’s haircut. Up against the conclusion of the Godfather saga, the only American mob epic capable of challenging the Corleones for their turf, and the movie that temporarily revived the big-screen Western, this deeply personal fairy tale would’ve fared about as well as its cutlery-fingered hero does against his tough-guy tormentors. But the presence of Awakenings and Ghost suggest that Edward Scissorhands could’ve carved out a place for itself among the year’s prospective Best Pictures, just as another Burton-directed Ed should have four years later. [Erik Adams]

1991: Boyz N The Hood

The actual nominees: Beauty And The Beast; Bugsy; JFK; The Prince Of Tides; Silence Of The Lambs

Boyz N The Hood made John Singleton the first black filmmaker and—for a time, anyway—the youngest person ever to score a Best Director nomination. But his searing portrayal of South Central L.A., and the lives of young black men warped and ruined by hopelessness, didn’t earn accompanying Best Picture recognition. Which is a shame, because it’s a milestone of American film, harrowing in its depiction of a community ravaged by ills the rest of the nation is all too happy to ignore. [Alex McLevy]

1992: Bram Stoker’s Dracula

The actual nominees: The Crying Game; A Few Good Men; Howards End; Scent Of A Woman; Unforgiven

Neck and veiny neck with F.W. Murnau’s silent Nosferatu as the finest big-screen interpretation of Dracula, Francis Ford Coppola’s sumptuous horror hit restored some of the idiosyncrasies of Bram Stoker’s classic novel (multiple narrators, the lack of a clear protagonist) while linking the appearance of the blood-sucking Transylvanian count in Victorian London to the dawn of psychoanalysis and cinema. Arriving in this hothouse of psychosexual subtexts, Dracula (Gary Oldman) transforms from a bone-white androgynous figure into an erotic predator. From its imaginative special effects (done entirely in-camera) to its stylized costumes, Bram Stoker’s Dracula is a feast; even Keanu Reeves’ atrocious accent has a certain charm. [Ignatiy Vishnevetsky]

1993: Groundhog Day

The actual nominees: The Fugitive; In The Name Of The Father; The Piano; The Remains Of The Day; Schindler’s List

Harold Ramis’ comic masterpiece is many things: a philosophical treatise, a winning romantic comedy, a sharp dose of existential horror. But at its core, it’s the ultimate vehicle for Bill Murray at the peak of his abilities. Ramis and Danny Rubin’s clockwork-precise script allows Murray to explore every facet of his well-trod public persona. The sarcastic asshole, the slimy lech, the deadpan depressive, and the manic clown all get their turn as Phil Connors takes his endless, blissfully unexplained steps toward finally becoming a better human being. [William Hughes]

1994: Naked

The actual nominees: Forrest Gump; Four Weddings And A Funeral; Pulp Fiction; Quiz Show; The Shawshank Redemption

The real travesty is David Thewlis being ignored in that year’s Best Actor competition, despite turning in one of the most galvanizing performances ever captured on celluloid. (It’s a wonder every print didn’t just ignite in the can.) But this discomfitingly dark portrait of one man’s relentless downward spiral, during which he inflicts his nihilistic worldview on half of nocturnal London, ranks among Mike Leigh’s finest efforts. He’d finally be recognized three years later for the slightly less lacerating Secrets & Lies. Why wait, though? [Mike D’Angelo]

1995: Heat

The actual nominees: Apollo 13; Babe; Braveheart; Il Postino; Sense & Sensibility

The definitive cops-and-robbers movie, Michael Mann’s masterpiece centers on two existentialist pulp archetypes—one a coldly professional career criminal (Robert De Niro), the other a troubled LAPD detective (Al Pacino)—as they pursue and evade each other. Notoriously, the men meet face-to-face only twice in the movie’s nearly three-hour running time; their operatic tension is the foundation for Mann’s terse art. From the set pieces to the supporting cast to the transcendent final shot, Heat is more or less perfect. But unlike some of the other films on this list, it was nominated for zero Oscars. [Ignatiy Vishnevetsky]

1996: Breaking The Waves

The actual nominees: The English Patient; Fargo; Jerry Maguire; Secrets & Lies; Shine

It’s rare for the Academy to get behind feel-bad films, and this is one of the feel-baddest offerings in Danish provocateur Lars Von Trier’s whole filmography, which is really saying something. Emily Watson rightly earned an Oscar nomination as a pious Scottish woman who struggles to accept her newly paralyzed husband’s extreme demand that she sleep with other men and tell him about it. Already breaking the rules of his own Dogme 95 manifesto, Von Trier delivers arguably his finest film, plus a magical realism-enhanced ending for the ages. [Alex McLevy]

1997: Boogie Nights

The actual nominees: As Good As It Gets; The Full Monty; Good Will Hunting; L.A. Confidential; Titanic

It would take Paul Thomas Anderson making a weighty historical epic to finally score a Best Picture nomination—and it’s no surprise the stodgy Academy would blanch at handing one to a movie that ends with Mark Wahlberg waggling a rubber dong. Still, Boogie Nights was an undeniably kinetic force, a movie that’s certainly indebted to Anderson’s forebears like Altman and Scorsese, but that also marks the arrival of an auteur precociously confident enough to be named beside them. Its nominations for Original Screenplay and the supporting performances of Julianne Moore and Burt Reynolds (the latter’s nod the kind of “playing against type” legacy tribute the Academy loves) don’t begin to do it justice. [Sean O’Neal]

1998: Rushmore

The actual nominees: Elizabeth; Life Is Beautiful; Saving Private Ryan; Shakespeare In Love; The Thin Red Line

Until the Best Picture field opened wide enough to accommodate The Grand Budapest Hotel in 2014, the Academy regularly treated Wes Anderson to consolatory Best Original Screenplay nominees, Perfect Attendance and Punctuality pins overlooking Anderson’s signature flair for sound and visuals. Those qualities snapped into place in Rushmore, the story of a prep-school overachiever attempting to fast-forward to adulthood while the grown-ups around him strain to slow their own lives down (preferably in-camera, with Cat Stevens on the soundtrack). Anderson’s breakout should’ve been his first Best Picture nod—at the very least, the Academy could’ve followed the MTV Movie Awards’ lead and invited the Max Fischer Players to stage the Best Picture montages for The Thin Red Line and Saving Private Ryan. [Erik Adams]

1999: Being John Malkovich

The actual nominees: American Beauty; The Cider House Rules; The Green Mile; The Insider; The Sixth Sense

With Being John Malkovich, music-video master Spike Jonze and sketch-comedy veteran Charlie Kaufman hatched a soulful head-scratcher from a high concept that could’ve served as wee-hours filler on 1990s MTV: In a half-sized floor of a Manhattan office building, a puppeteer (John Cusack) discovers a portal that transports him into the mind of actor John Malkovich. There’s layer upon layer of thought, humor, and invention to Being John Malkovich, all of which manifested in Oscar nominations for Jonze, Kaufman, and co-star Catherine Keener, but fell short of a Best Picture nod, despite sticking the landing on two failsafe Academy-flattering tricks: appealing to the vanity of an artiste like Malkovich, while stripping the same away in revelatory turns from bona fide movie stars Cusack and Cameron Diaz. [Erik Adams]

2000: Beau Travail

The actual nominees: Chocolat; Crouching Tiger, Hidden Dragon; Erin Brockovich; Gladiator; Traffic

Adaptations of classic literature are a staple of Oscar night, but how many use their source material not as a shortcut to prestige but as a prism for bold personal expression? With Beau Travail, the great French filmmaker Claire Denis transports Herman Melville’s final novella, Billy Budd, to the Horn Of Africa, and switches focus to the story’s antagonist, a stony officer of the French Foreign Legion (Denis Lavant) stewing with jealousy of—and repressed desire for—one of his new recruits. The hypnotic training sequences, all hard bodies in balletic motion, evoke the homoerotic subtext of the book, which Denis otherwise elliptically transforms into a poetic meditation on memory, regret, and longing. [A.A. Dowd]

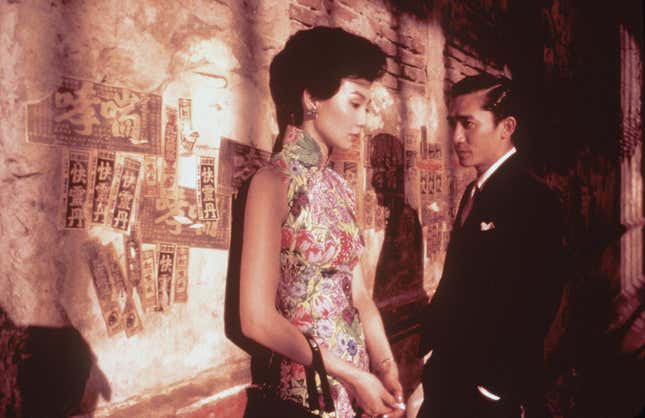

2001: In The Mood For Love

The actual nominees: A Beautiful Mind; Gosford Park; In The Bedroom; The Lord Of The Rings: The Fellowship Of The Ring; Moulin Rouge!

In a perfect world, Wong Kar-Wai’s rapturous Hong Kong love story would be an awards juggernaut: for its gorgeously smeary cinematography, its immaculate 1960s costumes and art design, and the smoldering old-school glamour of Tony Leung and Maggie Cheung, two blindingly beautiful international stars baring their souls as lonely neighbors contemplating an affair. At least getting snubbed put In The Mood For Love in good company: 2001 was such a superb year for movies that you could make an all-time great Best Picture lineup from the ones that missed nominations, including The Royal Tenenbaums, Mulholland Drive, and Memento. [A.A. Dowd]

2002: Morvern Callar

The actual nominees: Chicago; Gangs Of New York; The Hours; The Lord Of The Rings: The Two Towers; The Pianist

Lynne Ramsay came into her own as a visionary director with her passionate and poetic sophomore feature about a woman (Samantha Morton) who deals with her boyfriend’s suicide in unconventional ways. Narratively, the Scottish filmmaker eschews the first-person voice of the novel she’s adapting, instead dropping the audience into the passenger seat of Morvern’s journey, watching from the outside as her heroine struggles with how to approach life at its most unmoored. It’s audacious and unconventional, and all the richer for Ramsay’s willingness to throw out the rulebook and create her own. [Alex McLevy]

2003: The Son

The actual nominees: The Lord Of The Rings: The Return Of The King; Lost In Translation; Master And Commander: The Far Side Of The World; Mystic River; Seabiscuit

There’s a big gap between festival acclaim and Oscar glory. Look, for example, at the careers of Jean-Pierre and Luc Dardenne, the Belgian filmmaking brothers whose stark, unvarnished, socially conscious redemption stories routinely win big awards at Cannes while being roundly ignored by the Academy. The Son may be the duo’s finest hour: a tense, devastating drama about a carpenter (Olivier Gourmet) torn between vengeance and forgiveness when he’s confronted by the horrors of his past. The film’s morally charged suspense suggests Hitchcock by way of Bresson—a recipe for success in the Palais, but evidently not the Kodak. [A.A. Dowd]

2004: Eternal Sunshine Of The Spotless Mind

The actual nominees: The Aviator; Finding Neverland; Million Dollar Baby; Ray; Sideways

In a year that saw a Clint Eastwood boxing drama nearly sweep the top four Oscars categories, it’s no wonder that Michel Gondry’s idiosyncratic sci-fi breakup movie was ignored. A decade and a half later, love for this bittersweet love story has only grown; beyond its ingenious memory-erasure premise and the spot-on performances of Jim Carrey and Kate Winslet, Eternal Sunshine remains a nearly perfect study of the cycle from heartbreak to hope and back again. [Laura Adamczyk]

2005: A History Of Violence

The actual nominees: Brokeback Mountain; Capote; Crash; Good Night, And Good Luck; Munich

After decades of feverish genre work, David Cronenberg kicked off the stately passage of his career with A History Of Violence—a film that, like the rest of his Viggo trilogy, proved to be a more reserved take on his career-long obsession with the body, its needs, and its disintegration. Cronenberg works these themes with the same intensity of his earlier films, but with a newfound grace. Perhaps Academy voters were scared away by the film-opening execution of a preteen girl, the flashes of gore, or the explicit sex; the movie only netted nods for its screenplay and William Hurt’s supporting performance. Best Picture, meanwhile, went to Crash, bringing shame upon the institution for millennia. [Clayton Purdom]

2006: Marie Antoinette

The actual nominees: Babel; The Departed; Letters From Iwo Jima; Little Miss Sunshine; The Queen

Often pigeonholed as Sofia Coppola’s sassy, knowing commentary on celebrity culture, Marie Antoinette is more complex than a mere “take” on growing up privileged. Between the dreamy alt-pop soundtrack and the luxe set design and costuming, Coppola fits some stinging satire of know-it-all rich folks, and some heartbreakingly personal observations on how it feels to be at once scrutinized and overlooked. This is a rich and personal film, prescient in its understanding of what life would be like in the social media age. [Noel Murray]

2007: Zodiac

The actual nominees: Atonement; Juno; Michael Clayton; No Country For Old Men; There Will Be Blood

One-time MTV hotshot David Fincher finally earned the Academy’s stamp of approval with his most superficially prestigious movie, The Curious Case Of Benjamin Button. But the nominations arrived a year late. A perfect match of content to form, Zodiac finds this famously meticulous director tracing the zigzagging course of a decades-spanning unsolved mystery, his own compulsive fervor aligning neatly with that of cartoonist and amateur sleuth Robert Graysmith, who sets out to identify the elusive serial killer the San Francisco PD couldn’t catch. The first in 2007’s bumper crop of new American milestones, Fincher’s dazzling, labyrinthine procedural deserved to compete with those other towering portraits of murder and obsession, No Country For Old Men and There Will Be Blood. [A.A. Dowd]

2008: The Dark Knight

The actual nominees: The Curious Case Of Benjamin Button; Frost/Nixon; Milk; The Reader; Slumdog Millionaire

When two of the most beloved movies of 2008 failed to score Best Picture nominations, the outrage was so deafening that the Academy expanded the lineup to 10 movies the following year, in a transparent attempt to give populist box office smashes a fighting chance. Certainly, the Oscars should have saved room for the most adventurous of Pixar adventures, WALL-E. But Christopher Nolan’s mythic superhero sequel was the more befuddling oversight; nothing but pure genre snobbery could account for the exclusion of this intelligent, ambitious zeitgeist phenomenon—a grand exorcism of cultural anxieties in the shape of a slam-bang comic book spectacle, boasting an all-time-great villainous performance that’s smeared its crooked grin onto the collective psyche. [A.A. Dowd]

2009: Bright Star

The actual nominees: Avatar; The Blind Side; District 9; An Education; The Hurt Locker; Inglourious Basterds; Precious: Based On The Novel Push By Sapphire; A Serious Man; Up; Up In The Air

Jane Campion turns the beautiful, tragic romance between poet John Keats (Ben Whishaw) and his betrothed, Fanny Brawne (Abbie Cornish), into another of her period-piece marvels of human drama, à la the earlier and more evidently Oscar-friendly The Piano. Newly expanded from five to 10 available slots, the Best Picture lineup of 2009 could have easily accommodated Bright Star, which matched the writer-director’s poetic flourishes to a quietly passionate story, played out through a pair of superlative performances. Instead, the Academy made room for The Blind Side, surely one of the worst Best Picture contenders of all time. [Alex McLevy]

2010: Everyone Else

The actual nominees: 127 Hours; Black Swan; The Fighter; Inception; The Kids Are All Right; The King’s Speech; The Social Network; Toy Story 3; True Grit; Winter’s Bone

With just three features under her belt (one of them her graduate thesis project!), Germany’s Maren Ade has become one of world cinema’s rising stars. Toni Erdmann was her breakthrough, but that’s only because Everyone Else, about a young couple vacationing in Sardinia, lacked any sort of narrative hook that would grab people’s attention. It’s “merely” an incisive, uncompromising look at the ways in which people constantly recalibrate their identity relative to those around them, and how that process can wreak havoc on a romantic relationship. Watch it with a date at your peril. [Mike D’Angelo]

2011: A Separation

The actual nominees: The Artist; The Descendants; Extremely Loud & Incredibly Close; The Help; Hugo; Midnight In Paris; Moneyball; The Tree Of Life; War Horse

Asghar Farhadi’s twisty studies of deception and domestic duress work the brain and the heart in equal measure; they’re emotionally devastating dramas with the investigative urgency of murder mysteries. A Separation, his masterpiece, spins a tangled web of lies around two families caught in a nasty legal dispute, and the brilliance of the Iranian writer-director’s storytelling is how it divides its sympathies among all its beleaguered characters, even as it casts every version of events under suspicion. Farhadi won his first of two Foreign Language Oscars for the film (a rare feat), but his movies transcend nationality and language barriers. Their crushing power is universal. [A.A. Dowd]

2012: The Master

The actual nominees: Amour; Argo; Beasts Of The Southern Wild; Django Unchained; Les Misérables; Life Of Pi; Lincoln; Silver Linings Playbook; Zero Dark Thirty

Paul Thomas Anderson followed his violent, searching Western, There Will Be Blood, with a film that can feel as gargantuan and shifting as the images of the ocean that bookend it. Anyone checking in for the headline-grabbing potential of its Scientology inspiration would be quickly disappointed. Xenu shows up only in passing; Anderson sees in L. Ron Hubbard and his broken followers something much more personal, a parable for American invention, hucksterism, sexuality, and aimlessness. Oscar-nominated performances by Philip Seymour Hoffman and Joaquin Phoenix feed off each other like binary stars, matching the director’s supernatural ambition. Anderson was snubbed entirely. [Clayton Purdom]

2013: Frances Ha

The actual nominees: 12 Years A Slave; American Hustle; Captain Phillips; Dallas Buyers Club; Gravity; Her; Nebraska; Philomena; The Wolf Of Wall Street

This year’s Oscars are gratifyingly attuned to the achievements of Greta Gerwig’s Lady Bird (even given its ridiculous lack of an editing nomination). But a previous Gerwig project, her first co-writing collaboration with director Noah Baumbach, went ignored four years ago. Like Lady Bird, Frances Ha might look slight at first, but it accumulates power as it merrily skips through time, covering roughly a year in the life of a hapless twentysomething with both comic and melancholic vignettes. Baumbach’s work is often too prickly for consensus-driven awards, but Frances Ha is one of his most affirming and lovable pictures. [Jesse Hassenger]

2014: The Immigrant

The actual nominees: American Sniper; Birdman; Boyhood; The Grand Budapest Hotel; The Imitation Game; Selma; The Theory Of Everything; Whiplash

If you want to understand what made Harvey Weinstein powerful, don’t look at the movies and careers he claimed to have made, but the ones he destroyed. One of the great American films of the decade, James Gray’s The Immigrant wove a masterful drama of survival on the margins out of the internal struggles of a Polish immigrant (Marion Cotillard) in 1920s New York, her weak-willed pimp (Joaquin Phoenix), and his cousin (Jeremy Renner), an alcoholic stage magician—novelistically shaded characters whose contradictions and conflicts suggested Dostoevsky by way of Ellis Island. But the film was sold to Weinstein against Gray’s wishes (the two had a history) and was punished with a delayed bare-minimum release after the director refused to agree to a radical re-cut and a baffling happy ending. [Ignatiy Vishnevetsky]

2015: Inside Out

The actual nominees: The Big Short; Bridge Of Spies; Brooklyn; Mad Max: Fury Road; The Martian; The Revenant; Room; Spotlight

After a slew of toy-, animal-, and superhero-related movies, Inside Out broke the Pixar mold by focusing on emotions themselves—the feelings vying for control of homesick, hockey-loving 11-year-old Riley. No parent could keep it together as childhood memory keeper Bing Bong headed for oblivion in the Memory Dump. No child could fail to appreciate the permission Inside Out gave them to feel sad sometimes. Groundbreakingly empathetic and brilliantly imaginative, Inside Out won Best Animated Feature, but deserved a Best Picture nomination just for the Abstract Thought room alone. [Gwen Ihnat]

2016: The Handmaiden

The actual nominees: Arrival; Fences; Hacksaw Ridge; Hell Or High Water; Hidden Figures; La La Land; Lion; Manchester By The Sea; Moonlight

Park Chan-Wook’s whipcrack storytelling and painterly visual composition combined to uniquely rousing ends in The Handmaiden, a film of almost overwhelming abundance. It’s got it all: endless feints and double-crosses, keening eroticism, continent-hopping adventure, perverse humor, prismatic lead performances, tentacle porn—everything! It’s a turning point in Park’s rich filmography that netted no attention at all from the Academy, which gave Best Picture instead to La La Land, before calling an audible and giving it to Moonlight instead. (Good call.) [Clayton Purdom]

2017: The Florida Project

The actual nominees: Call Me By Your Name; Darkest Hour; Dunkirk; Get Out; Lady Bird; Phantom Thread; The Post; The Shape Of Water; Three Billboards Outside Ebbing, Missouri

Many of this year’s Best Picture nominees resemble subversions of traditional Oscar bait: The World War II epic is borderline experimental, the costume drama is about how the guy who makes the costumes is an unpleasant control freak, and even the big social-issue movie is also a horror film. The group could have been improved further by the addition of Sean Baker’s warm, funny, devastating portrait of the economic margins formed just outside of Disney’s Magic Kingdom. It’s a choice that would have felt forward-thinking in the moment; instead, in a few decades, it’ll be puzzling to consider that voters overlooked such a timely and original tearjerker. [Jesse Hassenger]